The key to understanding Amanda Knox is knowing how she delights at being the center of attention. In the opening seconds of this video one senses that giddy joy in being at the epicenter of her own story. She’s completely unaware that her involvement in the murder of Meredith Kercher does actually involve another person. Invariably Knox pays lip service to Kercher, by ticking off a few boxes. Kercher was friendly, a nice person, and with that done, she’s now free to marinade in her own story.

Anyone who has listened to Knox’s audiobook, in which Knox herself narrates her story, will have picked up what a performance artist she is. Even though Knox didn’t actually write her memoir herself, she sort of pretends she did. She regales the reader, in her mind, with her breathless adventures, and wows her audience with her impressive command of Italian. Because that’s what matters.

Was it Donald Trump who tweeted something along the lines of: Amanda Knox went to Italy to learn Italian. Well, she learned Italian…

It’s not enough to say Knox has an abnormal fixation with herself. It’s not sufficient to say she’s a self-centered narcissist. We have to ask why? What’s the seat of that deep psychological need, always, desperately wanting to be noticed? We may assume Knox was born that way, and that’s at least partly true. I mean, in the sense that as she grew up, she felt increasingly neglected. She was perhaps a very conscientious school kid, and I think she’s very conscientious in terms of dotting i’s and crossing t’s, in the academic sense. But a broken marriage and her mother jumping ship to shack up with a young stud, given the moral confines of the school community in which she was raised, created a psychological conundrum.

Knox soon found she was competing with her own young stepfather for her mother’s attention. She also learned how scandal could get you love and attention, something she experienced with her own mother. And she learned how to keep one’s cool, and surf the wave of scandal. We shouldn’t forget, though, that Knox’s insatiable appetite for attention was rooted in the excruciating inadequacies of a young daughter, and then a young teenager who, no matter how rigorously she obeyed the rules, simply couldn’t earn the love she needed. Every child deserves to be loved by their parents. When that love is simply not there, or replaced by a kind of cold, anal, homework ethic, then a hole forms in the soul of that person, a hole that can never be filled. It’s like a bucket with a hole in it. You can keep filling it, but it will always end up empty.

What Meredith Kercher did, was remind Knox in her fairy tale abroad about that hole. Kercher had two loving parents, who maintained very close contact with her despite them being divorced and her being abroad. Knox realized divorce wasn’t an excuse for her own parents to take such a minimal interest in her interior life.

One fathoms the shallowness of it all when eavesdropping on Knox’s mother visiting her in jail, just days after the murder. Her daughter’s implicated in a brutal murder, and yet the conversation – about lip balm, a nice new digs in Italy, and silly news reporters – couldn’t be more superficial. If this was all a joke to Edda, some issue that needed to be dealt with, like a test that needed to be marked, we can see how Knox would have no clue how to deal with complicated emotional or financial issues in her own life, other than to lie and mislead endlessly on these topics. She was simply extremely naive, and caught up in fantasies and fairy tales, primarily Harry Potter, but wasn’t a terrible storyteller either.

Now, I don’t mean caught up like a normal person. I mean so caught up, so immersed, that fiction begins to supplant reality. It’s someone who is completely out of touch with the real world, and with society, and all of this is exacerbated by an uptick in substance abuse – alcohol, marijuana, other recreational drugs [heroine perhaps, cocaine…]. Add to all this a sexual dimension, and a newfound “power” over Italian yobs, then one can see how being the center of attention in Italy could have gone to Knox’s head. From having a slew of Italian deplorables running after her, to the media salivating on her every outfit, her every kiss and smile, that’s not such a long walk in the walk after all, is it? That Amanda and this Amanda are still one and the same.

Society’s obsession with her mirrors Knox’s obsession with herself, and, ironically, our own fixations with ourselves.

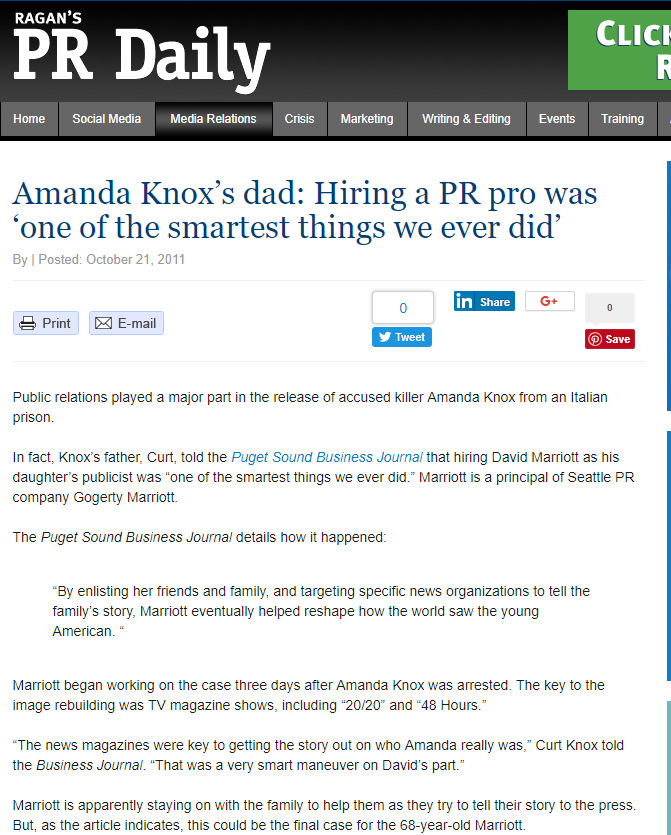

At about 4:55 in the video, Knox whines about not knowing how “big and all-encompassing” the media obsession regarding her was, until she “got out”. That’s not true. And far from being a victim of the media, her PR worked very skillfully to turn the tide in the media, especially from across the Atlantic, in her favor. And it worked. Not only did it work, it set the tone for her world record breaking publishing deal. So, far from the media being a wolf at her door, the media really saved her, and paved the yellow brick road that got her back home.

04:55: I finally saw it, I finally saw in the flesh…where…on the way out of the prison, I am being chased by paparazzi.

Shakedown: One has to do a sort of double-take here, as if a bang to the head might fix the glitch in our processors. Because this really IS alternate reality. In Knox’s reality, as soon as she was acquitted, as soon as the prison doors cranked open, she’s suddenly confronted by a phalanx of media, rapacious like wolves, their camera lenses gleaming like so many teeth and claws.

None of it’s true, but to expose the ruse for what it really is, and how cleverly the untruths are disguised in vague comments, we must slow it down and go through it bit by bit.

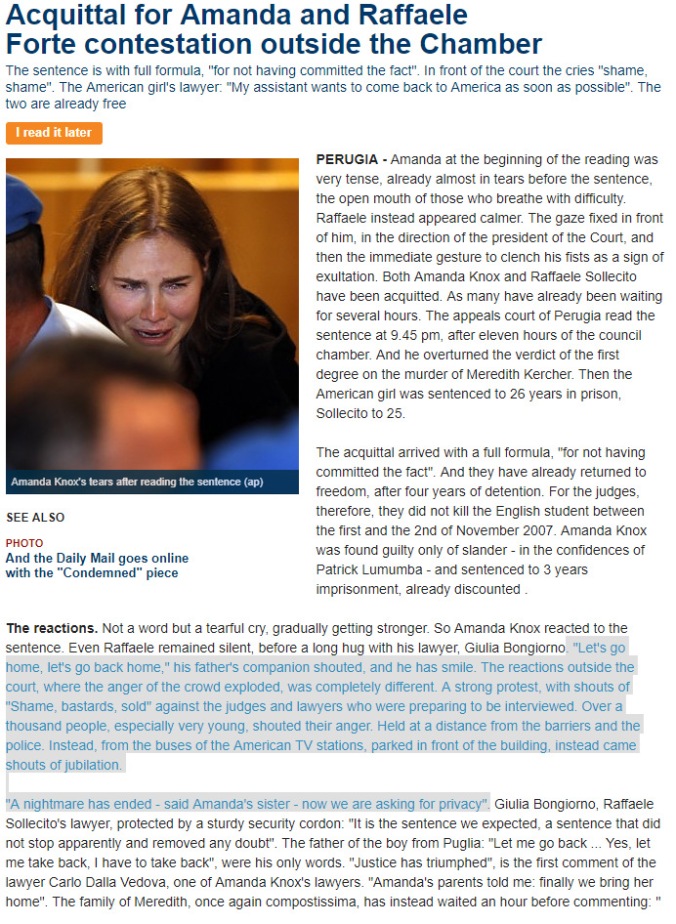

In the video, while Knox is talking, we see her being acquitted, and the tears and emotion following. The first factual issue to establish is when did this happen? Knox appealed her December 25, 2009 conviction in a trial that ran from November 2010 to her acquittal on October 3rd, 2011. The footage shown in the Facebook video are scenes outside court following her acquittal in October, 2011.

Note the date at the far right, top corner. Gosk was reporting from Seattle on October 4th, eagerly awaiting the return of America’s innocent sweetheart. Below that, holding her hand to her face, that’s Knox at Seattle airport, about to give a press conference [we’ll come back to that]. Top left, that’s the scene outside the court. Most of those people aren’t paparazzi, but students loudly protesting against Knox’s acquittal.

Say what?

On October 4th, the BBC summarized the media’s response to Knox’s acquittal. Fortunately, the BBC also provided samples from the European media, and not just American outlets. The above link is well worth serious study. At the screengrab below it’s made explicit:

Never before has the media aspect of a trial so outstripped the judicial aspect. The English media, who are on the side of the victim, the poor Meredith Kercher, renamed the pretty Amanda “Foxy Knoxy” just to underline her elusive craftiness. The American media, on the other hand, all support her… If you add this to the mess of the investigation and the disavowal of the expert [analysis], you see how far the story [and the court case] has gone off the rails of a judicial investigation and onto the more fanciful, popular ones of TV.

I guess Knox forget to add that part. And the American media washed like a tsunami over the other media, soon engulfing it. But what did Corriere della Sera mean when they said:

Never before has the media aspect of a trial so outstripped the judicial aspect…

Simply that this was the first time the media dominated the result of a court case. That sounds to me like the media played in Knox’s favor, doesn’t it?

Coming back to the photo of the large crowd outside the court, following Knox’s acquittal. What was happening there? In fact, of the three defendants, Knox had been sentenced to the most time in jail, not only for murder but for defeating the ends of justice and falsely accusing her boss. None of her co-accused did any of that, only Knox.

Now have a look at La Repubblica’s coverage, for October 4th:

After all that, let’s come back to Knox’s alternate reality, and why it’s alternate reality. What did she say on that video again?

I finally saw it, I finally saw in the flesh…where…on the way out of the prison, I am being chased by paparazzi.

The video is showing a mob outside the court, and reporters in Seattle. Where were the paparazzi when Knox left the prison? Well, there was at least one photographer stationed near the prison who managed to snap this photo.

Far from being hounded by paparazzi, when Knox arrived in Seattle, the first thing she did was give a press conference.

That dude with the beard, giving Knox a friendly punch of support, is none other than Dave Marriot, the man Knox’s father turned to just three days after her arrest, and a decision Kurt Knox described as the the best he’d made regarding his daughter’s predicament. Hiring an elite PR guru so soon after her arrest tells you a lot about what Kurt Knox thought about his daughter, and also, how urgently he felt he had to defend his own prestige – at the time Kurt Knox was a vice president of finance at Macy’s.

I finally saw it, I finally saw in the flesh…where…on the way out of the prison, I am being chased by paparazzi.

Do you see what she’s doing? She’s pretending to be wholly unaware of the Knox side of the paparazzi equation – where the media was organized, websites and blog sites were set up, all to defend Knox’s image. Her Facebook and MySpace pages were quickly deleted for the same reason – anyone think Knox was unaware of this?

Her lawyers were aware of it. The Italian court was aware of it.

On october 4th, 2011 the New York Times published their commentary on the issue, describing Knox’s acquittal as a 4 year battle “over an image”.

The British tabloids took to calling her Foxy Knoxy, adopting a nickname she had used herself on her Facebook and MySpace pages. (Her family said later that the nickname referred to her soccer skills, not her love life.) But by the time she was freed from an Italian prison on Monday, her public portrayal was very different: Many media accounts in the United States, at least, portrayed Ms. Knox as a nice young woman, a linguistics major at the University of Washington, who had fallen victim to the Italian justice system while on her junior year abroad.

No one can say for sure whether the painstaking and calculated rehabilitation of her image helped sway the Italian courts. Ultimately, it was an official report casting doubt on the DNA evidence in the case that led to her exoneration. But the media frenzy was mentioned by both the prosecution and the defense last month in court.

One of the prosecutors, Giuliano Mignini, complained in court of “the media’s morbid exaltation” of Ms. Knox and her former boyfriend, Raffaele Sollecito, who had also been convicted of the murder, along with a second man, Rudy Guede. “This lobbying, this media and political circus, this heavy interference, forget all of it!” he told the court, according to The Associated Press. Ms. Knox’s lawyers countered that their client had been “crucified” in the news media.

But the judges and jurors didn’t forget the media noise buzzing in and outside court, filling up the airwaves. And Knox’s lawyers were right; their client had been skewered by the Italian and British press, and rightly so. But that’s what made it so weird. On one side of the Atlantic [the Marriot side] Knox was an innocent angel, on the other, she was a she-devil. These contrasting narratives neutralized one another, and created doubt, which is gold to a defense case.

That being said, Knox was found guilty of slandering her boss, and her four year sentence upheld, so technically her acquittal didn’t mean she was innocent, just found to be not guilty of murder. So even the court that ultimately set her free, nevertheless regarded the attractive American student, as a liar.

So Knox saying, repeating, in 2018 that she “finally” saw it, “finally” saw the media in the flesh is a clever way of pretending she didn’t know about the media if she didn’t see it. Well, we know even before her acquittal, Knox was corresponding directly with journalists like the Guardian’s Simon Hattenstone from inside prison.

It was important that she hijack the UK narrative, because it was very negative towards her. So by having a UK journo from the fairly reliable Guardian at her beck-and-call was something of a coup.

At the same time, Knox’s mother was giving the same guy – Hattenstone – exclusive interviews. She did it following Knox’s original conviction, and after giving her own character evidence for her daughter in court, in June 2009, they didn’t have much to lose. Edda infected the UK narrative with “her side” of the story, and ultimately, the influence campaign and interference worked.

Hattenstone, believe it or not, was in Knox’s home in Seattle, reporting en plein air, as it were, when Knox faced the 2014 court verdict. In the same Guardian article, Hattenstone is clear about corresponding with Knox “since 2009” – in other words, for at least two of her four years in jail. Do you think Knox was only corresponding with Hattenstone? And would Hattenstone [and her parents, and her lawyers, and the PR man Marriot] not have updated her regularly on the media sentiment surrounding her? Would she not have regularly asked, and followed the news, from her in situ television?

I finally saw it, I finally saw in the flesh…where…on the way out of the prison, I am being chased by paparazzi.

5:27: I thought [after her acquittal] I was just going to go home. And for me, like, [looks up] it was just so overwhelming, the smell, I smelled home [starts crying] and it smelled like home. I smelled the grass, and the Earth and the rain. And it smelled so different than the place that I’d been in for so long, and…[looks up]…I was so overwhelmed by the smell, and then suddenly I was like, I guess I have to talk to a hundred people…

Video clip from October 4th, 2011 press conference at Seattle airport: I’m very overwhelmed right now. I was looking down from the airplane, and it seemed like everything wasn’t real [bursts into tears]. My family’s the most important thing to me right now [well, them and Dave Marriot]…and I just want to go, and be with them.

Shakedown: What is it with murder defendants and smells? When Oscar Pistorius [now a convicted murderer] did his PR, he spoke in a crybaby voice of smelling Reeva Steenkamp’s blood, as if by smelling it, he proved how sensitive he was to her death, and to her blood, presumably. It didn’t work.

When Knox trembles and sniffs as she talks about the smell of the rain [doesn’t it ever rain in Italy] it’s easy to feel emotional. But what are we being led to feel emotional about? That Nature’s touch is tender, or that Knox’s touch is? It’s a deception.

So what do we make of Knox pontificating about smell? She’s returned triumphantly to Seattle, and all she can do is smell. She can’t see anything, seems not to want to hear questions, she’s deaf and dumb to all, except smell.

In her memoir, Knox also spoke of being “hit immediately by the wet earthiness of Seattle…” I’ve no doubt that this is true. The issue is why are you talking about the most superficial crap, when the real issue is did you kill Meredith Kercher, and if you didn’t, why were you convicted? What happened? All of this smelliness is a distraction from those inquiries. And just as Oscar Pistorius howled with anguish whenever the prosecutor asked him difficult questions about his intentions in front of the toilet door, Knox also knows just when to turn on the water works.

What she really needs is an interviewer who says: Hold on, what the fuck are you so emotional about now, eleven fucking years later? Why isn’t it a happy memory, the memory of coming home, beating a 25 year prison sentence. Who cares about the rain and the dirt, how do you feel about your conviction for slander being upheld? Are you going to appeal that? Is it true that your mother is being accused of slandering the Italian police?

Why does thinking back on how you beat the Italian court system make you cry? Tell us, instead, how those emotions helped you win your case, how the sentimental PR flew your flag, how feelings flying in the face of very compelling circumstantial and forensic evidence, won your case for you?

Explain how the PR campaign after your conviction changed, and what lessons were learned that fed into winning your acquittal? How did your dress code change, in court, from the first trial to the appeal? Who was in charge of choosing your outfits, and Sollecito’s? Was cutting your hair, and Sollecito cutting his, also part of trying to appear more appealing in your appeal?

Who cares what she thinks about smells, what matters is what she thinks about being found not guilty of murder. How did that happen? But, she doesn’t want to talk about that. She wants America to see her the way they’ve read about her, as the poor American victim tortured by the Italian justice system.

…suddenly I was like, [crybaby voice] I guess I have to talk to a hundred people…

Taking to hundreds of people – that’s never been a problem for Knox. These Knox is taking appearance fees to talk to hundreds of people.

Even then, though, she was a person who sometimes sang at the top of her voice in restaurants, and as the comments in the previous post attest, headbanged to classical music despite being surrounded by [one images] a mature, cultured audience. Her constant loudness annoyed the hell out of her housemates. Even in prison, Knox strung her guitar and sang.

In court, Knox had no problem standing up and addressing the judge multiple times, in fluent Italian. A few days after Kercher’s murder, Knox was back in class, happy to read out her homework assignment to class. Her family, including her younger sister Deanna, gave press statements on the steps of the court, even went on Oprah, following her acquittal. Knox followed her acquittal with an exhaustive book tour, taking on the American talk show circuit. She was interviewed by heavyweights like Diane Sawyer and Chris Cuomo.

…suddenly I was like, [crybaby voice] I guess I have to talk to a hundred people…

Knox has since starred in her own eponymous movie, and she’s still at it.

Sorry, when was appearing in front of people something that ever scared her, or something she didn’t want to do? Through the murder of Meredith Kercher, Knox got to be exactly who and what she wanted to be: the star of her own show. Suddenly she’d been propelled out of insignificant anonymity, and who cared why, this was all about her and she loved it. She could act out and everyone would watch, take notes…how wonderful!

Meanwhile, at the press conference, Marriot and Knox met for the first time. Knox, probably saying exactly what he’d told her to say, her affect, precisely as he’d instructed her, said she just wanted to go home and be with her family; well, she’d been with them for many months in Italy. They’d been with her each day in court, and visiting her in prison. But it played well on TV.

06:13: And while I was overwhelmed with this, I was being asked to be ready to stand up to the judgement of others. [Soft, sympathetic piano music playing in the background]. I don’t get to be anonymous, ever. Ever. [Clip of Knox browsing for books on a public sidewalk]. And I think that’s a thing that people don’t get to think about very often. Because most people get to be anonymous at least…sometimes.

Knox was so desperate to be private, she wrote a book about her experience, providing details about her sex life in it, in the fact the word sex or sexy appears 116 times in her memoir.

…I was overwhelmed with this, I was being asked to be ready to stand up to the judgement of others… I don’t get to be anonymous…

People who want to be anonymous don’t court the limelight. People who are overwhelmed don’t hire PR people and teams of lawyers. As for being “ready” to stand up to judgement, in the immediate aftermath of the murder, Knox had accused her own boss, defied the police, even did gymnastic or yoga poses in the corridor of the police station while she and Sollecito were being questioned about Kercher’s murder.

In Italy, after the murder, the only person who wanted to go back to normal was Knox herself. All of Kercher’s friends left Perugia, and the villa itself emptied and closed. But Knox wanted to go back to school, wanted to continue living where she was, wanted to remain in Italy as if nothing happened.

Today, Knox continues to act in precisely that way – as if nothing has happened, and as if the notoriety surrounding her, is all about her. It’s not. The only reason people care about Amanda Knox is because of Meredith Kercher, because of the trauma she suffered when she died.

I was looking down from the airplane, and it seemed like everything wasn’t real…

Knox’s relationship with reality wasn’t that great in 2007, and today, has she really come into her own as a real person, living a real life, in the real world? Does she have a family? Does she have a job in the real world that doesn’t involve regurgitating her assumed Victimhood [a myth in itself]?

According to the latest version of herself, Knox has always wanted to be anonymous, that’s what Meredith and her weren’t fighting about, and why she wrote a book, and why she continues to trade on the legacy of the Kercher murder.

At the end of the day, that’s all she is, an afterthought, an echo, to someone else’s life.

Okay, so things were a bit dodgy, and didn’t quite add up, but Van Gogh said he cut off his ear, and said he’d shot himself. Why would say that if he hadn’t? That was the pertinent question that deserved an authentic answer. To get to it would require a deep dive, and that would take time and effort.

Okay, so things were a bit dodgy, and didn’t quite add up, but Van Gogh said he cut off his ear, and said he’d shot himself. Why would say that if he hadn’t? That was the pertinent question that deserved an authentic answer. To get to it would require a deep dive, and that would take time and effort.

Some people reckon Vincent van Gogh was

Some people reckon Vincent van Gogh was  Given the controversy surrounding “the ear incident”, Van Gogh’s 35-or-so self portraits are a valuable archive. Does he paint the side of his face missing the ear after December 1888? Does he see himself as mad? What is he saying?

Given the controversy surrounding “the ear incident”, Van Gogh’s 35-or-so self portraits are a valuable archive. Does he paint the side of his face missing the ear after December 1888? Does he see himself as mad? What is he saying?