Writing the opening to an original epic is hard. Anything that’s original, a unique product that’s uniquely your world is shit hard to bring into the world. It’s an art to get the pieces to fit and work together.

Once the original idea has become concrete and the juices are flowing, getting the first words on the page is the next step.

The trick is to transfer those sparkling eddies in the mind into compelling prose without losing the magic. Getting the beginning right paves the way for everything that follows.

In a way, the first words and paragraph are foundational to a narrative. Everything else is built on them. One wrong word and an entire franchise that could have been, that should have been, goes up in smoke.

In the unlikely event you do hit all the right notes right off the bat, well then you may go on to craft the next Harry Potter.

Blockbuster movies are faced with the same perils. How to get the optics just right, to set strong written narrative to motion picture that works.

So how do you get your epic to the perfect start?

This is my story, and it’s not necessarily about how to write the perfect opening as much as its about what goes into it. Like all art, mastery comes with time. You feel your way there after a lot of trial and error…

In 1987, every single day I would arrive at school with a fresh draft of the first chapter [rewritten], and in the first minutes before class, I’d hand it over to my best friend [the smartest kid in the class] for his assessment. And every time he’d say: “It’s good.” “Really good or just good?” “It’s really good.” “Is there anything you think I could improve.” “I’m not sure if you need to be so descriptive about pine-needles…”

I was never satisfied. I wanted it to be a lot better than good, so I’d go back and fine-tune. This went on every day for weeks, then months. When Alan finally said the opening was great, or perfect, I felt I’d pressured him into getting that response. I wanted to blow his socks off, not just write something that was good.

Over a long period I settled on a scenario. For the sake of authenticity, I wanted to anchor the setting in history. I found something like this at the local library [there was no internet or Wikipedia in those days]:

Saint Marcellus’ flood or Grote Mandrenke (Low Saxon: /ɣroːtə mandrɛŋkə/; “Great Drowning of Men”)[1] was a massive southwesterly Atlantic gale (also known as a European windstorm) which swept across the British Isles, the Netherlands, northern Germany, and Denmark (including Schleswig/Southern Jutland) around 16 January 1362, causing at minimum 25,000 deaths.[1] The storm tide is also called the “Second St. Marcellus flood” because it peaked 17 January, the feast day of St. Marcellus. A previous “First St. Marcellus flood” drowned 36,000 people along the coasts of West Friesland and Groningen on 16 January 1219.

An immense storm tide of the North Sea swept far inland from England and the Netherlands to Denmark and the German coast, breaking up islands, making parts of the mainland into islands, and wiping out entire towns and districts, such as Rungholt, said to have been located on the island of Strand in North Frisia, Ravenser Odd in East Yorkshire and the harbour of Dunwich.[2]

This storm tide, along with others of like size in the 13th century and 14th century, played a part in the formation of the Zuiderzee,[1] and was characteristic of the unsettled and changeable weather in northern Europe at the beginning of the Little Ice Age.

I was fascinated at the prospect of a modern civilisation experiencing the most extreme weather event possible on this planet: an Ice Age. Epic! What would that be like? What would it feel like? How would or wouldn’t technology cope? Would electricity still work when everything iced over? What would generate electricity? Would there even be electricity, or the internet, or TV? Imagine if there wasn’t.

I decided to set my first opening in the 8th century mainly because that was the beginning of Viking seafaring. The first written account of a Viking raid carried out on the abbey of Lindisfarne in northern England took place in 793.

Alan loved it the schema, but it still wasn’t perfect. Every word had to be placed right, it had to be lyrical and powerful. The sentences had to lock into one another so they formed a train that got up to speed quickly and evocatively. It also had to move you in a visceral sense. There were also other huge unknowns to deal with – characters, dialogue, knowing how much or how little description to use to paint each scene.

Once I had the symbolism set out, and the main body of what I wanted to say in place, I had to fiddle with small things; the narrative hairstyle, the footwear and clothing in the 8th century, ship and house design, basically the colour of the narrative shoelaces and how to tie them.

Eventually the changes were so small, Alan started asking: “This is exactly the same thing you showed me yesterday.” And I’d say: “It’s not, I changed a comma in the second sentence, and replaced “fizzled” with “dissolved.” “Also there were no sandwiches or collared shirts in the 8th century.”

I still remember now the opening I agonised over. I wanted the story to start off with a bang or a deafening screech, the loudest and biggest opening I could think of.

It went something like this:

A thousand Boeing 747’s touch down, out of time, onto a field in late 8th century Germany. The roar turns pine-needles to mush, the throat of the throbbing vortex of wind burns bright red as it vacuums all but one of our furry-clad great grandfathers from the northern seaside escarpment.

The entire village of Sleswig [Sleswick in the common tongue] explodes into splinters and ash. Housecats fly through the ether trailing racing-car miaws, pots spin into clattering frisbees, fiery hearths become flakes of inverted snow. The cremated community funnels through the screaming, smoking chimney; the maw gulps mountainsides, carves coastlines, and scrapes riverbeds into new shapes and configurations.

Brooks explode into shrieks of mist, ploughed Earth raked into seas of stinging sandblast. Inside this planet-altering holocaust, only the lanky figure of Heyerdahl, who’s out on the farm that day finds his feet in the chaos.

Out of all the Sleswiggians, it’s only his toes that find just enough purchase in the dirt to propel him along Lady Luck’s razor edge. Every slip on this hellish Thursday afternoon means his head dodges a javelin branch just in time, every stumble ducks through yet another toppling avalanche of hills or trees.

Through the cannonball gale, over liquidised leaves, under flying fenceposts, he scurries towards his children. He’s somewhere inside the stinging murk, a blurry figure, part racing legs, part windblown.

Then, somewhere in the maelstrom Heyerdahl’s grey-green eyes close in unconsciousness. A tendril of the storm lifts him into cartwheeling algorithms of survival.

Somehow he’s blown onto a boat, the boat pushed far from shore, sailing a course set by the fates. And so, the next morning, or whenever it was when day reappeared, Heyerdahl comes to flickering consciousness. His pale cheeks are sandpapered and scratched, his forehead bruised and burned, his wrists chafed and raw, his bare feet filled with splinters when he finds himself at sea. His long hair is green and brown with plant sap and soil.

His boat is blown clear across the Atlantic, and so when he arrives unheralded on the American coast, his skiff smashed to splinters on the booming reef, he becomes the first European to do so. He is the last of kin on the edge of the world. He steps off the strand, determined to find his way home following the coast.

He heads north, thinking he’s still in the Old World on the German coast. If Heyerdahl fails to find his way home, to a home that no longer exists, or fails to survive this perilous leg back to the Old World, you and I will never exist. And so, across time and space, we must sit on his shoulder and cheer him on, so that whoever he may be, may be, and so that one day, so will we…

You can see how ambitious it all was, right? And there was plenty of room for improvement, to add something not thought of, to subtract something that was overstated or repeated, not so? Of course, this version’s not exactly how it was written because I lost the original manuscript, twice.

In the next part I’ll deal with how that happened, and the process of resurrecting the DNA of the story after a long period of hibernation and mourning.

I should probably add that this opening that I spent months perfecting, agonising over, doing literally hundreds of rewrites and subjecting poor Alan to each morning at school, never made it into the actual narrative.

About thirty years later when I rewrote the epic, I found myself back at the ranch in terms of wanting the best possible initiating chapter. The set-up was all important to tell the reader: this is something new and bigger and totally EPIC. But how to execute not just a Big Wow Beginning, but The Biggest Wow Beginning That’s Possible To Conceive.

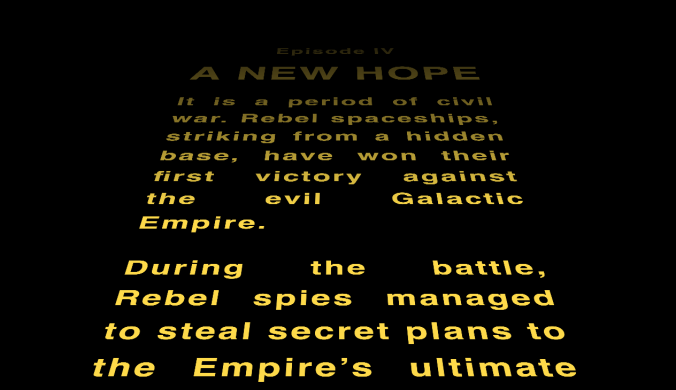

George Lucas was faced with the same dilemma in Star Wars, and solved cleverly [or clumsily] with the famous yellow scrawl and John Williams’ amazing score.

I wanted the same majestic opening, the sound of trumpets, the text burning the page like yellow scrawl rising over a darkened cinema audience.

In Bloodline Murmurs of Earth although the original start written three score and two years earlier isn’t there, the echoes of those early scribbles are. The scenario I ended up going with is completely different, but the idea of racing legs, flapping furs, pine trees and loud noises is still there. Does the opening work?

Read Bloodline Murmurs of Earth at this link.